[Author’s Note: Hey, there! It’s been a hot minute (which these days means exactly the opposite of what I remember it meaning) since my last newsletter. The last few months have been difficult at work because of a temporary contracts attorney shortage. More on that later. I’ve had this newsletter in the hopper for a while, and I’ve finally found a little spare time to get it published. Enjoy.]

If you know me even a little bit, you may have guessed I’m the type of person who makes a pro and con list for almost every decision I make. I read, study, create financial spread sheets, check the reviews, ask everyone I know (and some I don’t) what they think of the idea, what they’d do in my situation. Then I do a preliminary pro-con list in pencil. Then I sleep on it, second guess myself, erase half of one column and add a bunch a stuff I didn’t think about the first round.

My pro-con list for making the move to Minnesota from Denver in the middle of my life was a far more complicated algorithm. I’ve talked about how being closer to my mother as she ages was key, how the real estate market made it almost impossible not to sell, and how a decent legal job presented itself. Now, let me tell you about my health. Or lack thereof, at times.

As many of you know, I’m a breast cancer survivor. Twelve years ago at the age of 40, I was diagnosed with triple negative breast cancer, a rarer and more aggressive form of the dumb, yet insidious, disease. I gritted my way through a lumpectomy, chemotherapy, and radiation. It was a scary time, but the treatment was over within nine months. My hair grew back, and I resumed my life. There are now days when it seems like a distant oddball thing that happened in a dream. Some longer-term side effects became ingrained, though. One of them was anxiety about my health. My surgeon and oncology team at the Rocky Mountain Cancer Center saved my life, and trapezing beyond that safety net felt like an oversized con on the list -- written in all caps, bolded, AND underlined. Because, despite all scientific probabilities to the contrary and annual oncologist pronouncements of No Evidence of Disease (NED!), most cancer survivors given truth serum will confess that they believe in their heart of hearts it’s going to come back. I believe this in my heart of hearts. Any move away from Denver had to factor in good access to health care.

The opportunity to live close to the Mayo Clinic tipped the scales.

Folks, I gotta tell ya, it’s everything it’s cracked up to be. If you don’t know anything about this world-renowned Mecca for top-notch patient care and medical research, you should. It’s a model of what health care should be in the United States.

The Mayo Clinic was born from a cornfield collaboration between Franciscan nun Mother Alfred Moes and English immigrant physician William Worrel Mayo. Mayo ended up stationed in Rochester to care for Union soldiers during the Civil War. After the war, Dr. Mayo’s wife, Louise, weary of frequent moves, told her husband that they were staying put. They had two boys, William and Charles, who also entered into the medical profession. After a tornado hit Rochester in 1883, the Mayos and the nuns worked together among the rubble of the young town to care for the many wounded. Mother Alfred and her Franciscan order decided the Doctors Mayo needed a proper hospital. They raised the money and built Saint Marys Hospital. The Mayos, dedicated to advancing science-based medical treatments, quickly turned Saint Marys and their own medical office a mile away into a destination where patients could rely on surviving surgeries and other medical professionals could learn how to do more than just sawing off limbs. Saint Marys Hospital became part of an ever-expanding network of buildings developed by the Mayos to accommodate medical specialists, researchers, laboratories, and medical students. The Mayos and their acolytes pioneered things such as washing hands and wearing surgical gloves to prevent infections, creating a medical record system that all care providers could reference when treating a patient, and inventing medical devices that allowed for organ transplants. They placed pathologists in labs next to operating theaters so a patient’s disease could be diagnosed before she woke up. If you want to learn more how such a cutting-edge medical campus came to be in the middle of nowhere, I recommend Ken Burns’s documentary, The Mayo Clinic: Faith-Hope-Science, available on PBS. Don’t worry, it’s only two hours.

The Mayos’ and the Franciscan Sisters’ mantra from day one was that “the needs of the patient come first.” This led to a system built to incentivize medical professionals to take their time in treating the patients rather than running up the medical bills. The Mayos paid their medical providers fair salaries rather than a cut of the take – something that’s still done today. Doctors were rewarded for sharing information about patients rather than jealously hoarding it to prevent the patient from going to another doctor down the street. If a physician needed to bring in a specialist, they would bring him or her in right away so the patient wouldn’t have to make another long journey.

All of this led to an institutional ethic and operation that is customer-service oriented and efficient. I can vouch for this. I’ve now had about a ten visits to Mayo, and I’ve been astonished every time at the high-thread-count quality of the care. Some examples:

· My entre into the system was with a primary care provider. She spent about an hour with me just asking a lot of questions about my health history and lifestyle while at the same time downloading every electronic record she could find and assigning assistants to send out record request forms when she couldn’t find them online. By the end of that hour she could recount my surgical history (which dates back to 1976!) better than I could. By the time I hit the check-out station, the admin had several appointment dates lined up to see a provider at the Breast Clinic, a radiologist for an endoscopy to check on my GERD issues, and a gastroenterologist to go over the results of the endoscopy, whatever they might be. She sent me downstairs for a blood test and to collect a Cologuard colonoscopy kit. Before I drove out of the parking ramp, the Mayo Clinic app was pinging me with the results of the blood test. My PCP was also texting me via the app to see if I’d like to see a dietician to address the high cholesterol result, which she could see from my records had developed into a bit of stubborn issue. I said yes. The next day, another admin texted me a menu of appointment dates to choose from. No calling and being put on hold while the receptionist at the specialist office fields thirteen other calls coming in.

· My trip to the Breast Clinic was similar. The doctor spent an hour going over my history, doing an exam, and explaining how the clinic operates. She provided a yearbook-style chart of my “breast team” -- RNs, nurse practitioners, ultrasound techs, physicians, radiologists, oncologists, gene therapists, and other providers who would be involved in my annual checkup. (All except one were women, natch.) Was I due for an annual mammo? Yep. Well, we can get you in today. After the squishies, the mammo tech apologized and said I might not see the report until the next morning since it was already late in the afternoon. The next morning, as promised, the app pinged me. I opened up a report that had, literally, 324 radiology images of my boob included. The only time I remember ever seeing mammo images before was when my radiologist back in Denver pulled me into her office in a follow-up visit to show me my tumor. All 324 images showed NED, BTW. Nevertheless, my breast team quarterback texted to say that I had dense breast tissue and next year they would schedule an MBI scan, a type of scan developed at Mayo to detect the smallest of tumors.

· When I met with the gastroenterologist, he also spent an hour with me, hand-drawing the upper half of my alimentary canal on one side of a sheet of paper and a decision flow-chart for my treatment choices on the other. For this visual learner, it was like he was speaking some secret medical love language.

Because Mayo is also a research institute, I’ve already been invited into a couple studies. I’m not opposed to donating my body to science, even before I’m dead, so I always say yes. To date, I’ve helped with the development of a new medical tool to more easily and cheaply diagnose Barret’s Esophagus, and my DNA is about to be sequenced in the hopes of figuring out how having this information in a person’s medical records can lead to more targeted and less onerous treatment options for future breast cancer patients. I can’t think of a better way to pay it forward.

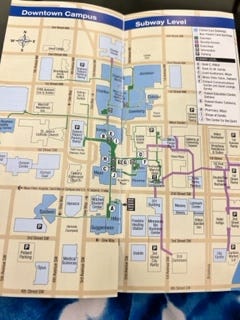

Mayo’s facilities take up most of downtown Rochester, and they are stunning. Going there feels like checking into a high-end hotel. All of the facilities are connected by an underground subway system, so it’s easy to get to any of the buildings, even in winter.

Although this is now my local health care network (just 1.7 miles from my house), Mayo is a destination for people worldwide seeking the best medical care available. I now understand why.

Beautiful drift Holli. I also am grateful for Mayo. I just wish anyone could get in. About the only way you can become a new patient there is a super emergency or become a Hormel employee.🤣🤣 Ken Burn’s program on the Mayo Clinic on PBS is an awesome way to add to what Holli wrote. Love you daughter ❤️

Thank you